South-east Asia: Nepal has eliminated rubella in a 12 year public health campaign.

For a long time, rubella was considered quite harmless: a bit of a fever, some red spots on the body, and after three days, it’s all gone. Although complications are possible, they are rare in children. However, it’s not as simple as it seemed, which became clear at least in 1941, when the Australian ophthalmologist Norman McAlister Gregg realised that rubella during pregnancy can severely damage the eyes of the unborn.

Not only the eyes, but also the heart and the ears of the children in the womb often suffer from the virus; almost no organ is safe. The risk is particularly high during early pregnancy as British physician and statistician Julia Bell showed in 1959 (Bell, 1959).

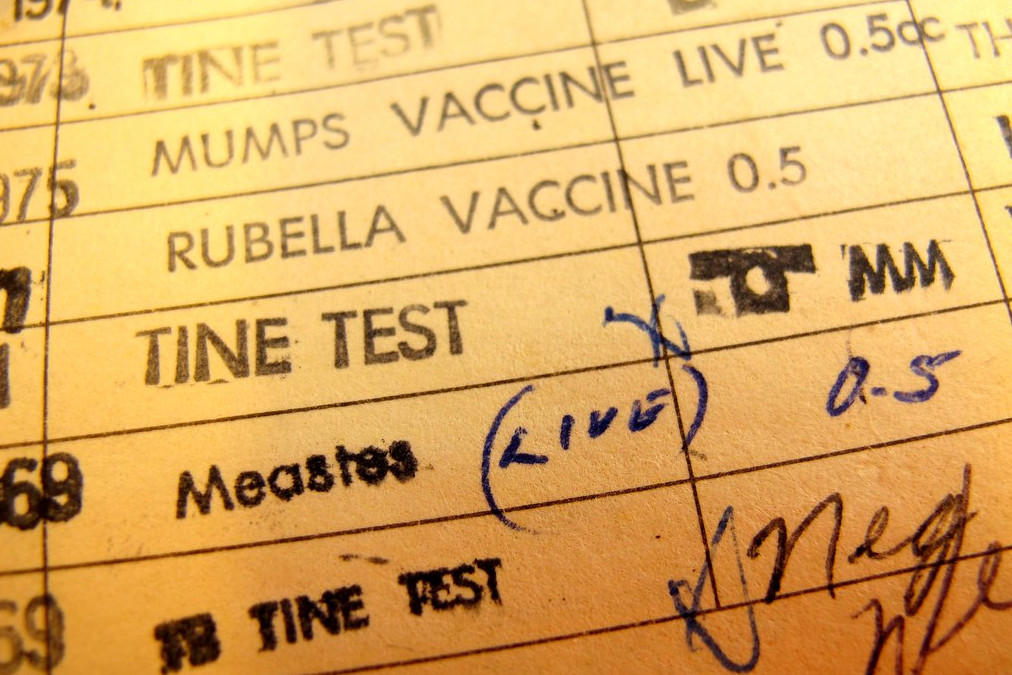

Until the virus was isolated and a vaccine could be developed in 1969, a last rubella epidemic ravaged through Europe and the United States. The U.S. Department of Health estimated that twelve million Americans got infected with rubella during that outbreak. As a consequence, eight thousand children were born without hearing, almost four thousand without hearing and blind (CDC). In 2006, Stanley Plotkin–physician, vaccine researcher, and co-developer of the rubella vaccine–wrote about this time, “Those of us who were practicing pediatrics or obstetrics during those years remember with poignancy the many tragedies we witnessed as families struggled with decisions about therapeutic abortions and severely damaged infants.”

Having the vaccine, those tragedies could be a thing of the past. To really fight spreading the disease, as many people as possible need to be vaccinated, at least once, and better twice. In the case of rubella, the second dose simply aims at people for whom the first dose had failed. Finland began in 1982 to systematically vaccinate children and young adults twice (Peltola, 1994). After twelve years of doing so, it became the first country to eliminate rubella. The vaccine was voluntary and free of charge.

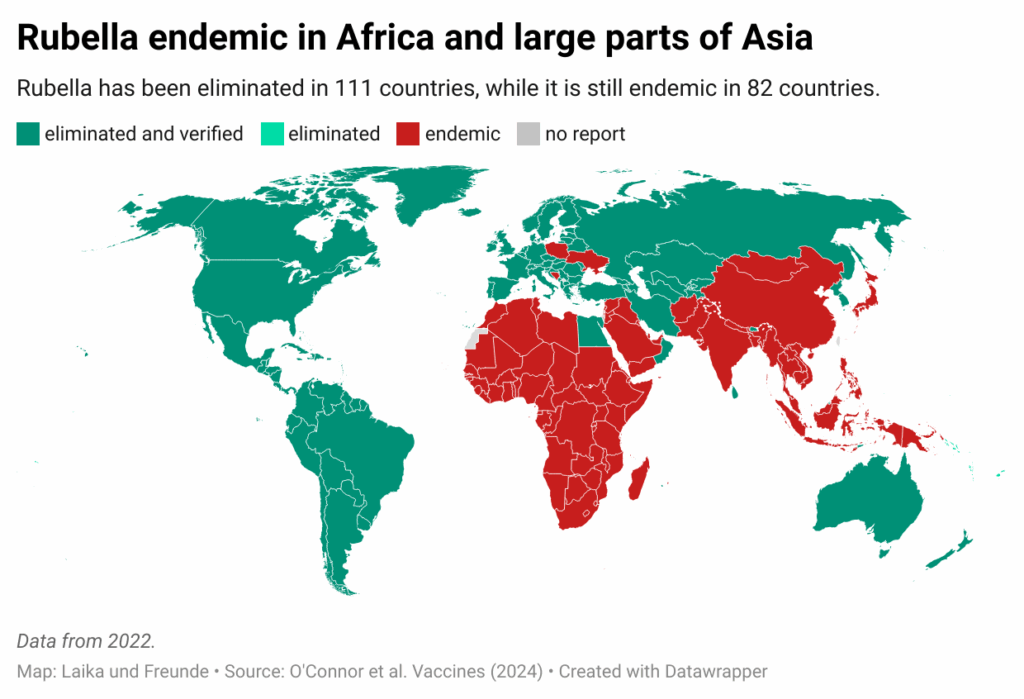

Over time, more countries started a rigorous vaccination program similar to the Finnish success model, and it is getting tougher for the virus: the American continent eliminated rubella in 2015 (PAHO, 2015). With some exceptions, the disease has been eradicated in Europe, and many Asian countries have been progressing a lot in the last decade. Since August, Nepal has been among the rubella-free countries (WHO, 2025). Nepal introduced the vaccination campaign in 2012, and despite huge obstacles–like the 2015 earthquake and the COVID-19 pandemic–today about 95 percent of the people in Nepal have received at least one dose.

Could rubella be completely eliminated from Earth? The chances are high. Rubella is only transmitted between humans; no other animal is a host for the virus. Worldwide eradication is a realistic possibility, and the success achieved with smallpox shows the way.

Other infectious diseases that only occur in humans are polio, measles, mumps, diphtheria, and pertussis. There is a good chance these diseases will be eliminated one day. The rubella vaccination is usually given in combination with substances against measles and mumps. This reduces cost and effort. Infection numbers for the three diseases run mostly parallel.

But as long as the virus or bacteria causing an illness are occurring in humans, the risk of another outbreak is real. On one hand, people can bring the infection from abroad, on the other, vaccination rates can go down for a variety of reasons and rip holes in the protection of a population. A single re-import can lead to a severe problem. It needs high vaccination rates and tight observation of cases.

In other good news: Kenya eliminated sleeping sickness (WHO report).

©Niko Komin (@kokemikal)